In a small city in upstate New York, a sculpture garden sprawls across the landscape of a decommissioned air force base. The sculptures, 21 in all, are far enough apart that a map is useful to get from one to another. Pleasant walking trails lined with newly planted apple trees provide a link between the works of art.

One of the most striking sculptures is called “Persephone.” It soars 24 feet high, and thin branch-like tubes in colors of red, yellow, and orange burst from the sculpture’s base, resembling a burning tree or a spectacular, slow-motion fireworks display.

On the day I visited, the colors popped against the blue summer sky, appearing nearly fluorescent. I had the park almost entirely to myself. A woman in a white skirt strolled nearby, the dog at the end of her leash straining to break free and chase a muskrat that had scurried into a patch of tall grass.

It wasn’t always this peaceful here, and it’s history adds intrigue to a visit, and makes it truly unique local destination.

Griffiss International Sculpture Garden is named after the air force base that formerly occupied these grounds. The base was decommissioned in 1995, opening up 3,500 acres of land at the northeast border of Rome, New York, a city of 40,000 people located 45 miles east of Syracuse.

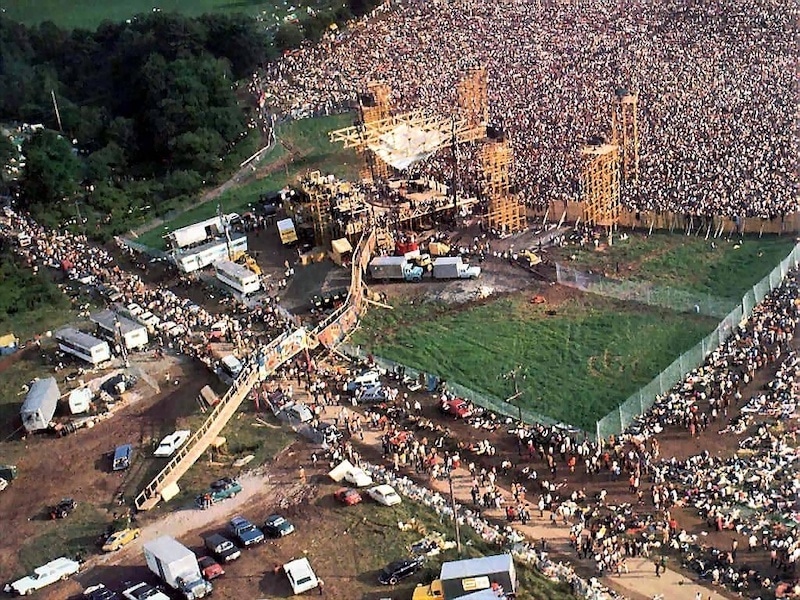

Four years after the base’s closure, and many years before an open-air sculpture garden appeared, the former Griffiss Air Force Base was the site of Woodstock 1999, which has become known as one of the most disastrous music festivals of all time.

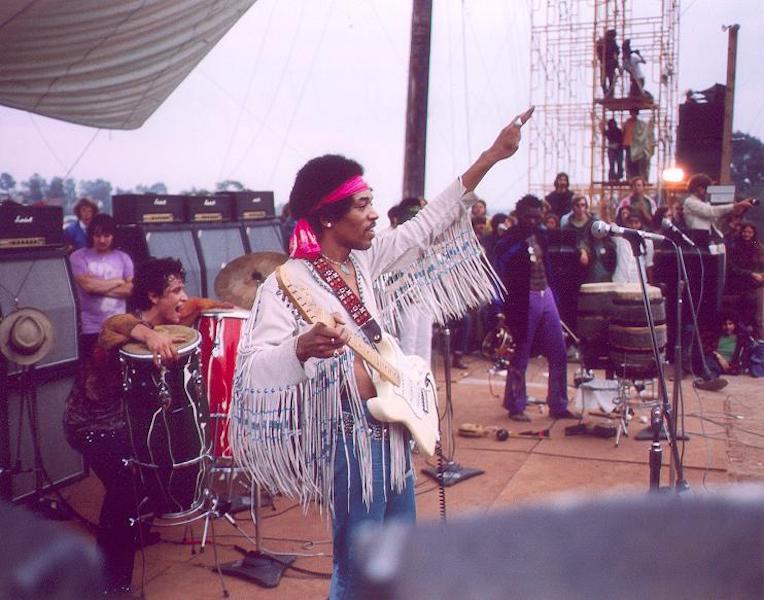

The event was held to commemorate the 30th anniversary of the original Woodstock Music & Art Fair, held on a farm in Bethel, N.Y., 140 miles south of Rome.

The original festival took place from August 15-18, 1969 and while it had its problems, it ultimately went down in history as a peaceful endeavor that marked a generation intent on peace.

Woodstock ’99 has a different legacy.

Searing summer temperatures and a frustrating lack of shade were met with long lines for water fountains. Food and bottled water were severely overpriced so, fueled by frustration, heat, and the blind stupidity that takes root in a crowd mentality, festival-goers smashed water fountains, destroying the only source of free water.

Kid Rock incited violence by telling the crowd to throw plastic water bottles up on stage. Limp Bizkit played “Break Stuff” and encouraged people to do so.

A misogynistic vibe permeated its way through the crowd of 220,000, culminating in several allegations of sexual assault. A story of a young crowd-surfing woman being pulled down to the ground and raped is just one of the disturbing stories.

As the Red Hot Chili Peppers played their set on the final day, the crowd set fire to cars and vendor tents and Woodstock ’99 devolved into riots and looting.

I grew up in Rome, N.Y., but I was not a part of this catastrophic event–at least not until it was all over.

By 1999, I was traveling whenever and wherever I could and was only coming home for visits in between my travels. At the start of this particular weekend, I was heading out of town on a Greyhound bus. Matt and I had accepted teaching jobs in South Korea and I was on my way down to Philadelphia to meet his family before we left.

Inside the bus station the day before the festival began, the scent of patchouli mixed with body odor and hung on the stuffy air. White kids with thick dreadlocks sprawled on top of dirty backpacks on the floor reminded more of Haight-Ashbury than my sleepy hometown.

Never before had it been a way station for the tie-dye clad, Birkenstock-wearing crowd that I witnessed streaming off buses that day.

For the first time in my lifetime, Rome was a destination for something other than the World Series of Bocce or historical sites of the Revolutionary War.

When I returned from Philadelphia, the Woodstock 30th anniversary festival was over, and stories of disorder and violence were spreading on the local news.

The previous week, I had answered a want-ad posted by the Department of Labor, looking for a post-festival clean-up crew. The pay for just three days work was good and I still had another few weeks to go before starting my new teaching job; even longer before I’d receive a paycheck.

I reported for duty the following day, about 24 hours after the last of the festival-goers had straggled off the air base.

Unlike the original Woodstock festival, which took place on a rolling green farm in the Catskill Mountains, the main stages of Woodstock ’99 were located on the tarmac of the old air base. For the festival crowd, this tarmac radiated even more heat than the 90-plus temperatures, and provided an ugly terrain.

For me that day, it didn’t matter what the ground looked like because every inch of it was covered in trash.

A sea of plastic made up the first layer: empty water and soda bottles lay fallen on their sides on top of dirty paper plates and cardboard pizza boxes. Torn food wrappers fluttered in a breeze that was beginning to stir up the smell of old garbage. There were so many abandoned coolers and tents that it looked almost like people had fled suddenly.

The clean-up crew organizers lined us up side by side to span the width of the festival grounds, like a spoofed reenactment of Hands Across America. They gave each of us a pair of blue plastic surgical gloves and an extra-large, thick, black garbage bag.

We were instructed to pick up the garbage piece by piece, and once our bags were full, to leave them in place to be collected by another crew.

For eight hours, we filled bag after bag of garbage. The morning was warm and clear. I remember thinking, as I faced the field of trash in front of me, that it was a perfect beach day. I also remember being afraid that I’d be stuck by a needle, my only protection between me and the endless pieces of trash a flimsy pair of plastic gloves.

I befriended a 16-year-old girl who was working to my left. We marveled at the sheer amount of trash. “Didn’t they have garbage cans during the festival?” we asked each other.

Asja was a junior in high school and had immigrated from Bosnia just the year before. She introduced me to her parents, who were working to her left and whose English was not yet as fluent as their daughter’s.

We chatted about learning English and teaching English. We compared what we knew about the bands that had played at Woodstock over the weekend: we both knew Alanis Morrisette and Jewel, but neither of us could name a song by The Tragically Hip. Neither of us knew yet how wrong the concert had gone.

By the end of the day, the army of cleaners had filled thousands of trash bags. Looking around, it seemed like we had hardly made a dent. I had signed up for three days of clean-up but when I woke the next morning, I could hardly get out of bed. From bending down all day and grasping pieces of trash, my lower back was on fire, my fingertips raw. I couldn’t even close my hands into a fist because my palms were so sore. I felt sorry that I wouldn’t see Asja again but I didn’t go back.

Nearly 20 years went by before I set foot on those grounds again. By then, it was officially known as Griffiss Business and Technology Park. The tarmac where Woodstock had taken place was still there, now part of Griffiss International Airport.

The sculpture garden is located south of the airport. I was visiting to research an article I was writing for the local tourism board.

Besides the airport and the sculpture garden, the complex is now the site of dozens of businesses that employ more than 5,000 people.

The businesses are mundane—a credit union, Avis Rent-a-Car, a Family Dollar Distribution Center—but far enough away that the sculpture garden stands alone. If you didn’t know this used to be an air base, you might just think an empty field was repurposed for the sake of art.

So where do these sculptures come from?

Twenty miles southeast of Rome, in the city of Utica, there’s a warehoused-sized facility called Sculpture Space, which awards residencies throughout the year and provides artists with the space and the equipment necessary to create massive works of art.

All of the sculptures featured at Griffiss International Sculpture Garden have come out of Sculpture Space. The artists hail from countries around the world, including Poland, Argentina, Turkey, and the United States, creating international harmony via art, perhaps achieving the peace that the original Woodstock meant to evoke.

Throughout 2019, several 50th Woodstock anniversary festivals were planned. All of the official ones fell through, leaving the chaotic Rome, N.Y. event as the last and perhaps final one to commemorate that original iconic weekend in the summer of 1969.

That’s probably just as well. Times have changed. Duplicating “3 Days of Peace, Love, and Music” seems increasingly less likely in the world. But at least we can find some solitude, walking among beautiful works of art that occupy the space where a military base used to be.

- Photo Credits:

- Jimi Hendrix at Woodstock 1969; People wrapped in blankets: Photograher Mark Goff (Public Domain)

- Monument to Woodstock: Photographer Marc Holstein (Creative Commons)

- Stage and Crowd at Woodstock 1969: Public Domain