[Updated January 27, 2022] If you’re interested in visiting historical sites related to the fight for women’s right to vote, the Women’s Rights National Historical Park in Seneca Falls, NY is the perfect destination.

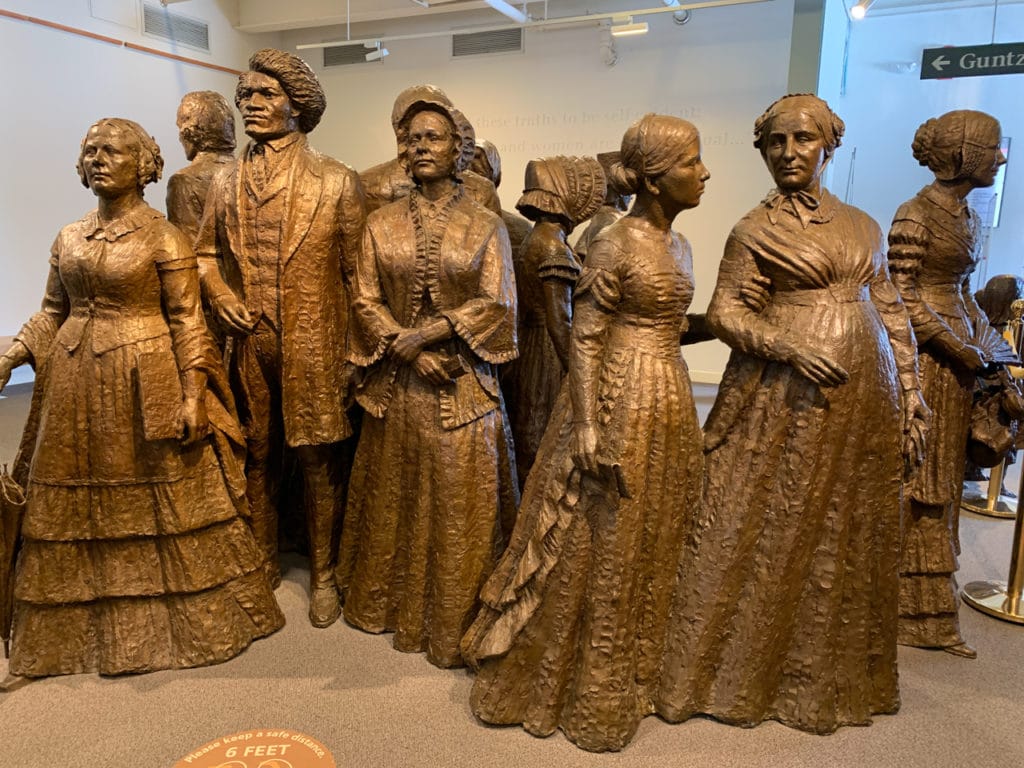

It was in this village in Upstate New York where the Seneca Falls Convention took place in 1848, after being organized by suffragists Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott. It was the first ever Women’s Rights Convention in the U.S. Supporters traveled from far and wide to attend, including Frederick Douglass who, after escaping slavery in 1838, devoted his life to abolition and the women’s rights movement.

Seneca Falls is located in the Finger Lakes region of New York State. It’s on the northern shore of Cayuga Lake, with the town of Geneva to the west and Ithaca to the south.

The Women’s Rights National Historical Park is made up of a collection of historic sites in Seneca Falls and by visiting these sites, you can put yourself into the shoes of the women and men of 100 years ago. Read on to find out more about women’s suffrage and the historic Women’s Rights National Historical Park in Seneca Falls.

Note: This post is entirely about the Women’s Rights National Historical Park. For information about things to do, and where to eat and stay, please read my post, Things to do in Seneca Falls. If you’re interested in exploring the region’s wineries or breweries after brushing up on women’s history, you’re in a good spot for that, too.

Seneca Falls and the Women’s Suffrage Movement

In the mid-19th century, Seneca Falls had become somewhat of a center of activism. The anti-slavery movement was gaining traction, and many prominent abolitionists called Seneca Falls home, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

At this particular point in history, upper middle-class white women such as Stanton were denied the same basic rights that white men enjoyed. Among other things, they couldn’t own property and they couldn’t vote. The idea for the first Women’s Rights Convention in the U.S. evolved from Stanton and her peers’ frustration at their lack of equality.

What to See at the Women’s Rights National Historical Park

The collection of sites include the Visitor Center, Wesleyan Chapel, and two historic homes. The sites fall under the auspices of the National Park Service. Admission is free to all sites.

The Visitor Center

I recommend beginning your tour of the Women’s Rights National Historical Park at the Visitor Center. Located next to Wesleyan Chapel, the Visitor Center is easily identified by the Waterwall, featuring words from the Declaration of Sentiments etched underneath a cascading waterfall.

On the Visitor Center first floor, a dynamic sculpture represents attendees of the Convention. You can also view a short educational film in the theater called Dreams of Equality, which is also currently available on YouTube. Additionally, there is a bookstore and gift shop.

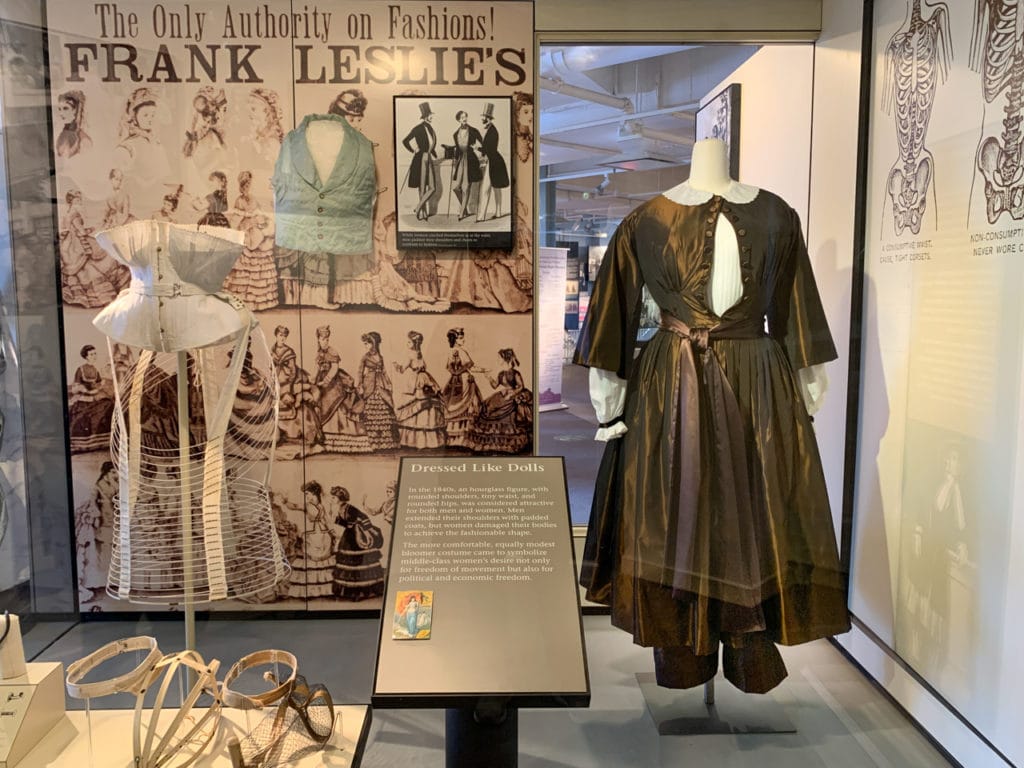

The second floor contains exhibits about various themes surrounding women’s history and women’s rights. Topics touched upon include slavery, politics, religion, family, employment, sports, and fashion.

Here you can learn more about the Seneca Falls Convention, the struggle for equal pay, the uncomfortable and damaging clothing such as corsets that have burdened women throughout time, and much more about the timeline of the women’s rights movement.

Open Thursday – Sunday 10 a.m. – 4 p.m.

136 Fall Street, Seneca Falls

Ph: 315-568-0024

Wesleyan Chapel

Just next door to the Visitor Center is Wesleyan Chapel. Built in 1843 by a congregation of abolitionists, it is a simple, sparse structure made famous as the site of the first Women’s Rights Convention in the U.S., an event that drew around 300 attendees.

We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men and women are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator; with certain inalienable rights; that among these rights are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness…

Declaration of Sentiments

The event kicked off with a reading of The Declaration of Sentiments, written by Stanton and the other organizers of the convention. The document was modeled after the Declaration of Independence and called for women’s equality in all areas including jobs, family life, and education.

I first visited Wesleyan Chapel in March of 2018. Because it was Women’s History Month, a slew of special events were happening and I attended a talk given by an actress playing Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

She was dressed the part, wearing a buttoned-up somber dress and her hat, gloves, and shawl ensured that only her face and a sliver of her neck was visible. When she took her place at the podium, she invited the small crowd to fill in the wooden pews in front of her and began telling stories about her life.

She described how she’d been fortunate to receive a good education even though women couldn’t enroll in college at the time. Her father was a lawyer and a judge and by reading his law books, she was able to debate fine details of the law with her father’s clerks.

Stanton also briefly described her later life: she married Henry Brewster Stanton, a lawyer and abolitionist. They eventually had seven children and moved to Seneca Falls, where she was buried in the numbing grind of being a housewife and mother.

This was in interesting way to get to know “Elizabeth,” and it helped put history into context as I sat in the place where Stanton actually would have spoken to the Seneca Falls Convention attendees in 1848.

Open daily 10 a.m. – 4 p.m.

136 Fall Street, Seneca Falls

Elizabeth Cady Stanton Home

Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s home is a modest white farmhouse located on a quiet street in Seneca Falls. She and her husband and children moved here in 1847 and stayed for 15 years. Because Stanton was often stuck at home with her kids and her domestic duties, she invited other activists to come to her. Her home became a gathering place to organize and strategize and she took to calling it “The Center of the Rebellion.”

Visitors can tour the two-story home and a view the parlor, the bedrooms, and the family furniture. The house has been largely refurbished to its original condition; some furniture is original while some has been replicated. The home was sold in 1862 when the family moved to New York City.

Open seasonally (closed during the winter)

32 Washington Street, Seneca Falls

M’Clintock House

A few miles away in Waterloo, the M’Clintock House is open seasonally to the public. Mary Ann M’Clintock was a fellow suffragette and one of the organizers of the Seneca Falls Convention. It was in her home that the Declaration of Sentiments was drafted.

Open seasonally (closed during the winter)

14 Williams Street, Waterloo

Nearby, an 1848 gathering at Jane Hunt’s home first sparked the idea for a women’s rights convention. The Hunt House is under renovation and not yet open to the public.

401 East Main Street, Waterloo

Take a Guided Walking Tour of Historic Sites

Guided tours led by park rangers are occasionally available. Call or check the website for more information before you go and if you are able to, definitely join one. On the tour, you’ll walk from the Visitor’s Center to Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s house, which is about a mile in distance.

On my guided tour, the park ranger discussed the history of Seneca Falls as a mill town and the many goods and products that used to be produced there.

He also talked about Seneca Falls history, telling how the area was originally populated by the Cayuga tribe, whose villages were destroyed by colonialists in the 18th century. The waterpower was harnessed in the 19th century, making it a hub for mills, factories, and tanneries, and in the 1940s, director Frank Capra visited and was so moved that it became his model for Bedford Falls in the classic movie, “It’s a Wonderful Life.”

He also described what’s known of Stanton’s daily life in the small town. She had a gaggle of unruly children and their home was the only one on the street at the time, leaving her isolated by the tedium of motherhood and housework.

We also stopped to look at a statue that commemorates the exact spot where Susan B. Anthony met Elizabeth Cady Stanton. They were introduced by Amelia Bloomer, herself an advocate for women’s rights and an outspoken critic of the uncomfortable clothing women of her time were expected to wear.

If you don’t take the walking tour, it’s still very easy to see the statue, which is located at East Bayard and East Spring Streets, just a few minute’s walk from the Visitor Center.

When to Visit Women’s Rights National Historical Park

The hours of business vary and the historic homes are closed during the winter. In addition, Seneca Falls is located in the center of New York state, where winters can get very cold and snowy. Any sites that are open may close during inclement weather.

I do, however, recommend visiting in March, since that’s Women’s History Month and the park offers a variety of special exhibitions, lectures, and tours. Another month to mark on your calendar is July when Convention Days are held to commemorate the 1848 event.

See here for the most up-to-date calendar of events.

Racism in the Women’s Suffrage Movement

As is the case with a lot of U.S. history, the stories that get told are often based on who is telling them. A lot of details are left out or forgotten. This is the case in many of the stories about the struggle for voting rights.

While black men were granted the right to vote in 1870, many were beaten and lynched when they attempted to exercise their rights. While white women proudly marched in parades in support of their right to vote, they relegated black women to the back rows or made them hold their own separate parades altogether.

And while suffragists such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton advocated for the women’s right to vote, their fight is littered with a legacy of racism. Though the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention called for “social, civil, and religious rights of women,” the “women” referred to were primarily middle-class white women.

In fact, no black women were present—or invited to—the convention so they could make their voices heard. To Stanton and many of her peers, the issue of disenfranchised black women fell under the problem of race rather than gender.

Stanton was also opposed to the 15th Amendment which gave black men the right to vote. And despite the fact that Frederick Douglass gave a passionate and convincing speech at the Seneca Falls Convention in support of women, Stanton did not repay him in kind by supporting his right to vote.

As realization of the whitewashing of American history becomes (to me) more and more apparent, there seems to be no end of influential prominent black men and women throughout history whose names are lesser known or altogether unknown. The women’s suffrage movement is no exception.

The names of black women suffragists are harder to come by in historical texts, even though women such as Ida B. Wells, Mary Church Terrell, and Sojourner Truth devoted their lives to the cause, often sacrificing their own safety to do so.

And while the white women mentioned above devoted their lives to the suffragist cause, it’s important to recognize that they often did so at the expense and safety of marginalized people.